Pitfalls of retrospective studies in medical records for reimbursement

Using medical records for reimbursement data? Watch out for pitfalls

What if a company needs data for reimbursement right away? Can it use existing medical records instead of setting up a study and waiting for the results

Using medical records sounds like a great idea. Mine the data in them, and get follow-up results now without having to wait. And you don’t have the costs of setting up a clinical study. Cheaper and quicker – what could be better? But is it really a valid option? How reliable are medical records in this context?

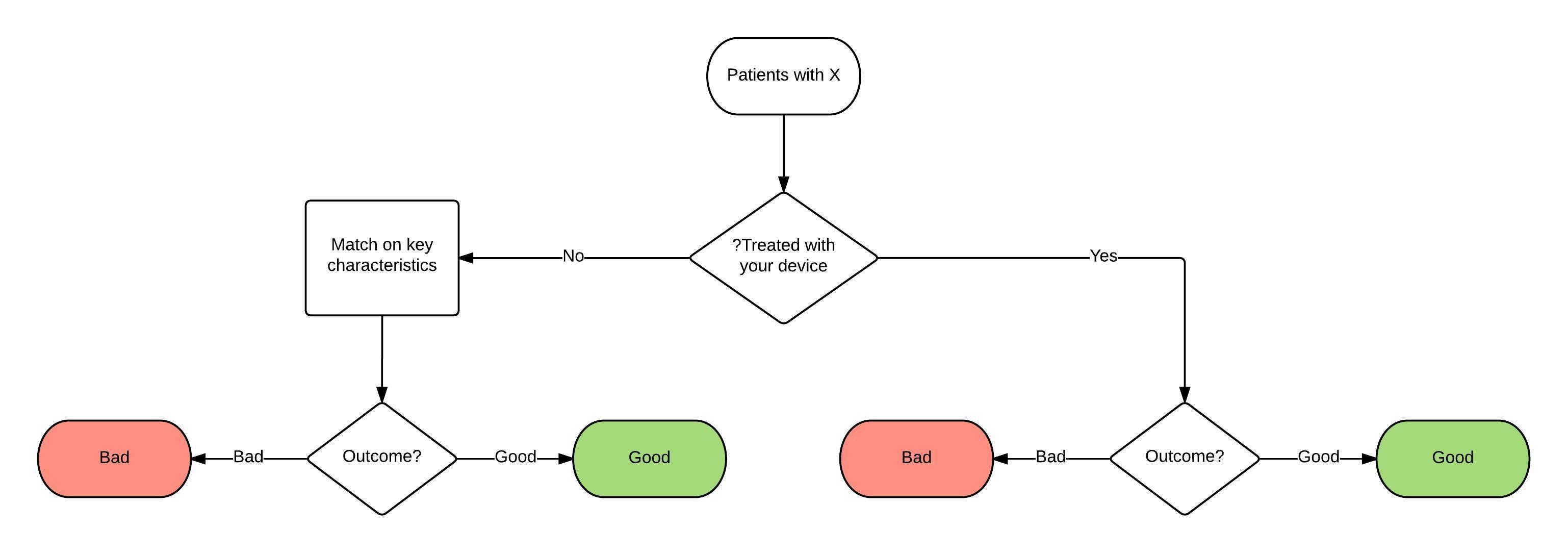

Take the simplest approach to making use of medical records first. Patients are seen and, if suitable, are treated with your product. At some later date, there is an outcome. For simplicity we will assume that the product is a device used in a hospital and the outcome is either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ (Figure 1) but the principles apply to tests or more complex outcomes and outside hospitals, too.

This is known as a case series. There are several significant problems with this study design:

- it is impossible to tell what the base population from which these patients come.

- how do you know which patients get referred to that centre or that doctor?

Something about that population might be described, depending on the circumstances. For instance, if the hospital serves everyone in a small town and is the only hospital there, it is likely that referrals for common conditions are representative of the population of patients as a whole.

Once patients are referred, the doctor and patient make an individual choice of treatment. A decision may be made to continue trying drug treatments if the patient is reluctant to undergo surgery or the doctor feels that in a particular case the balance of advantage for the patient lies in conservative treatment.

The process by which these decisions are made is often subjective, involves an interaction between the opinion of the doctor and that of the patient, and may be complex and hard to describe.

It is seldom clear and protocol driven as it normally would be in a clinical trial. Even where it could have been described, medical records do not always record the factors fully, if at all.

Interpreting the outcomes with historical data is problematic as it is not possible to be sure that the patients being offered the treatment using your device are typical of all (superficially) similar patients.

There are so many potential variables:

- a patient with severe headaches who is willing to continue drug treatment may be suffering from slightly less severe or less frequent headaches, so the condition may be milder, even slightly;

- or the patient may be more stoic than another, and report milder symptoms than another patient would in the same circumstances;

- a patient desperate to have symptoms alleviated may opt for a non-medical intervention and because of their desire for relief may experience relief regardless of the effectiveness of the device – the placebo response.

Some of these problems may be partly addressed by, for example, treating all consecutive patients who are referred during a given period and ensuring they conform to specified criteria, to eliminate factors which are not described or recorded or even known and which may influence the choice of treatment.

Another type of problem with this design based on historical data is that it is non-comparative. We do not know what would have happened to these people had they been treated in another way. In a comparative trial, this is dealt with by allocation to an intervention or a control group (preferably random allocation) so that the outcomes in two groups similar in every respect except one (the treatment) are compared and statistical allowance made for differences which might have arisen by chance.

There is also no blinding: the patient and the doctor both know what treatment the patient had. This affects both the choice which either might make and the results which either might report. Usually the bias which results favours the new treatment, but the fundamental problem is that the effect of any bias is unknown.

Even more to the point, a payer will be able to discount results on this basis.

Finally there are the problems of what is in the medical records. These records are kept for administrative and legal purposes, and as notes to remind healthcare professionals of what was done. They are frequently unstructured. They are usually incomplete. Typically they contain words which are undefined, and used in different ways by different people. Pain may be described as ‘severe’ because the patient describes it thus, one doctor may interpret the patient’s symptoms as ‘severe’ when another would describe it as ‘moderate’.

All these issues make the results of case series reported in medical records unreliable, and perceived as such by payers. They may be useful to illustrate the experience of a centre, encouraging other similar centres to adopt the procedure, but they are not useful as the basis for a reimbursement case.

Control group alternatives?

The drawbacks of not having a control group can be partially addressed by one of three manoeuvres.

- Records can be obtained for a group of similar patients treated at the hospital prior to your device becoming available: these are ‘historical controls’. The key problem, as with the other manoeuvres described below, is showing that the patients in the control group are ‘the same as’ the patients receiving your device. A particular problem with historical controls is that clinical practice tends to change over time: new tests and new medicines become available, new papers are published, new guidelines are developed, new medical records systems are installed. The further back in time you have to reach for historical controls, the more unreliable they may become as comparators..

- A second source of controls is a group of patients treated at the same time in another clinic in the same hospital or in another hospital: these are ‘concurrent controls’. In this case, there is more likely to be differences other than the treatment, which may be unknown, between the two groups of patients. Different patients may be referred to different hospitals or, within a hospital, to different doctors. Formal and informal protocols and recording may differ, as may definitions.

- A third source of controls is the published literature. This has the same disadvantages of concurrent controls, with the added difficulty of more limited availability of data than in medical records and because of the lag in collecting and publishing data, those of historical controls. The advantage compared with concurrent controls is that published figures may have a wider coverage, with bigger sample sizes from a wider range of hospitals, although this may not be the case.

- Finally, and probably best in these circumstances, is to match patients not treated with your device to patients treated with your device on as many relevant factors as possible: age, sex, severity of pain, length of time since diagnosis, number of previous failed treatments etc. (Figure 2). Even if all these factors are recorded, all the relevant factors may not be known—factors other than the ones you think of may influence outcomes, even if they are not known. This is the strength of random allocation. If you have to reach back further into the past to collect the information on matched patients, there are the problems of historical controls and if you have to obtain information on patients treated in other clinics or hospitals there are the problems of concurrent controls.

Figure 2: Controlled trial involving case series with matched controls

The position outside hospitals is in principle the same, but records in office-based practice or primary care tend to be even less good than in hospital, magnifying the difficulties outlined.

Best avoided

None of the fixes outlined here are more than very partial solutions. Apart from the theoretical problems of using case records as a source of data on effectiveness, payers using a health technology assessment approach will find it easy to reject the results if it is inconvenient to accept them. Using the retrospectoscope is convenient and cheap but should be avoided if at all possible.