Validity of trial results

My pivotal trial results strongly support my product. I can’t understand why we have been told by an insurance company that they don’t consider the results relevant and have rejected our application for reimbursement.

The problem here is validity: do the results apply to the decision-maker’s situation? Can the conclusions drawn from a study be relied on to make a decision?

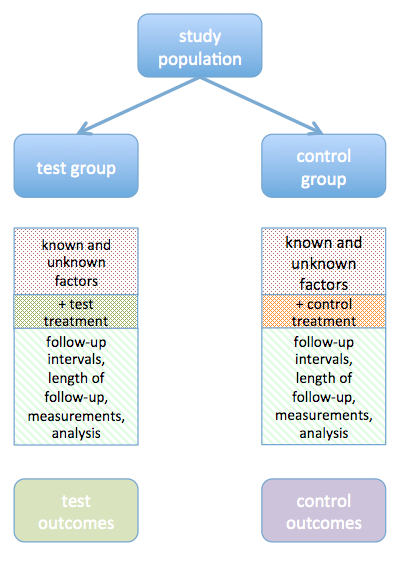

There are two sorts of validity: internal and external. Internal validity is the degree to which the study design protects the results from systematic error (bias). This includes the methods used to select and allocate study subjects, to collect information, and to analyse the data. As Figure 1 shows, study design is intended to equalise all factors that may affect the actual or measured outcome between the two groups, other than the difference in treatment. When the study design allows factors other than the treatments being investigated to differ, the comparison of outcomes in the two groups loses its force.

External validity is the degree to which the results of a study apply to people who did not participate in the study. To what extent are the study subjects similar to the population for which the treatment is being proposed? A study is externally valid (or generalisable), if it allows unbiased inferences to be drawn to the population of interest to the payer. For example, if the ethnic origin of the study population, treatments prior to entering the study, or stage of disease are very different from those of the population for which reimbursement is being considered, the results may not be considered sufficiently relevant to allow a conclusion to be drawn. A fairly common problem is that a study is carried out in a centre of excellence which receives tertiary referrals: the characteristics of such a group of patients may be significantly different from those of patients referred by a primary care doctor to a typical secondary care hospital.

A general problem with clinical trials is that in order to eliminate as much variation as possible and allow the ‘true’ effect to be detected, inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied. Care is needed to avoid creating a study population that is so untypical of the people seen in a normal working environment that the results cannot be relied on by either a doctor or a payer. Other problems include more intensive follow-up than in everyday practice, and greater adherence of patients to aspects of treatment, monitoring, or rehabilitation than is likely to occur outside a research setting.

An important aspect of generalisability is the treatment received by the control group. If this is not the same as the treatment the group currently receive, a payer may reject the study findings as insufficiently relevant. This can occur as a result of differing clinical practice between countries. Sometimes the comparison group is treated on the basis of best practice guidelines: if this practice is not typical, a payer may find the comparison misleading both clinically and economically.

When considering sponsorship of studies, we recommend that you develop a dummy business case for reimbursement in each of the main markets of interest before committing to a study design. This business case will describe the real-world target population and standard clinical pathways in each country for these patients. A proposed study design can then be assessed against the requirements of the business case to ensure that you will be able to leverage the results to optimise reimbursement. Studies sponsored by device manufacturers should be of interest to investigators and methodologically sound, but it is also important that they are fit for purpose in supporting commercial objectives.